When is a Migraine headache really a Migraine?

When is a Migraine headache really a Migraine?

“My head hurts…It must be a migraine!” Is a common complaint amongst many patients in neurology clinics and Austin pain clinics alike. However, not all headaches have the same triggers, causes, or treatments. In specific, a migraine is a severe headache that may be commonly associated with nausea and/or light and sound sensitivity. This type of headache is distinctly different from cluster type headaches (pain behind the eye) and tension type headaches (pain across forehead) which may be discussed in more detail with your physician.

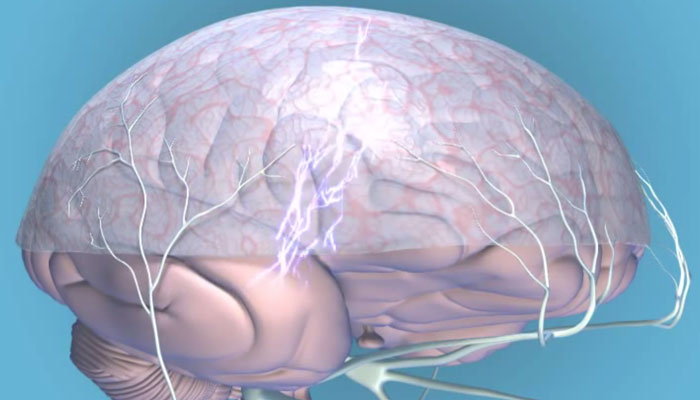

So when is a “migraine” really a migraine headache? The once popular ‘vascular theory of migraine’ purported that migraine headaches were a cause of dilatation and vasoconstriction of cerebral blood vessels is no longer considered mainstream [1-3]. More reflective of current research is the idea that migraines are caused by ‘cortical spreading depression’ or a wave of electrical activity sweeping across the brain.

This electrical wave activates a nerve system known as the ‘trigeminovascular system’ (TVS) which is a network of nerves that can irritate the pain-sensitive lining of the brain (the meninges). The TVS explains the distribution of migraine pain, which often includes the front and back of the head and the upper neck [4,5].The prolongation and intensification of migraine pain is propagated by the inflammatory response (neurogenic inflammation) triggered by the TVS [6].

What role does genetics have with migraine headaches? Migraine headaches are in most instances inherited. Subtle abnormalities, involving membrane channels, receptor families, and enzyme systems have been linked to migraine in certain groups and individuals. The importance of inheritance in migraine has long been recognized [7]. One early general population based study found that the risk of migraine in relatives of migraineurs was three times greater than that of relatives of non-migraine control subjects [8].

How common are migraine headaches? Migraine is a common disorder that affects up to 12 percent of the general population [8]. It is more frequent in women than in men, with attacks occurring in up to 17 percent of women and 6 percent of men each year [9,10]. Migraine is most common in those aged 30 to 39, an age span in which prevalence in men and women reaches 7 and 24 percent, respectively [10]. Migraine also tends to run in families. Migraine without aura is the most common type, accounting for approximately 75 percent of cases.

What is a migraine aura? About 25 percent of people with migraines experience one or more focal neurologic symptoms called the migraine aura. Auras are most often visual, but can also be sensory, verbal, or motor disturbances. Visual auras may either appear as a bright spot or as an area of visual loss or geometric shapes and zigzagging lines may often appear. [12]. Less common than the visual and sensory auras, is the language or dysphasic aura that causes transient language problems that may run the gamut from mild wording difficulties to frank difficult speaking [13]. Traditional teaching is that migraine aura usually precedes the headache [13]. However, prospective data suggest that most patients with migraine experience headache during the aura phase [14]. It may also occur without an associated headache.

Can I feel a migraine starting? A migraine prodrome (forewarning) occurs in up to 60 percent of people 24 to 48 hours prior to the onset of headache i.e. euphoria, depression, irritability, food cravings, constipation, neck stiffness, and increased yawning [10].

How does a migraine progress? Migraine is a disorder of recurrent attacks. The attacks unfold through a cascade of events that occur over the course of several hours to days. A typical migraine attack progresses through four phases: the prodrome, the aura, the headache, and the postdrome [11]. The headache of migraine is often but not always unilateral and tends to have a throbbing or pulsatile quality, especially as the intensity increases. As the attack severity increases over the course of one to several hours, patients frequently experience nausea and sometimes vomiting. Many individuals report sensitivity to light or sound during attacks, leading such migraine sufferers to seek relief by lying down in a darkened, quiet room.

What is a migraine postdrome — Once the spontaneous throbbing of the headache resolves, the patient may experience a postdromal phase, during which sudden head movement transiently causes pain in the location of the headache. During the postdrome, patients often feel drained or exhausted.

What precipitates or exacerbates a migraine? An evidence-based review concluded that stress, menstruation, visual stimuli, weather changes, nitrates, fasting, and wine were probable migraine trigger factors, while sleep disturbances and aspartame were possible migraine triggers [15]. All of the probable and possible migraine triggers except aspartame were also general headache triggers.

In a retrospective study of 1750 patients with migraine, approximately 75 percent reported at least one trigger of acute migraine attacks [16]. In order of descending frequency these included:

- Emotional stress (80 percent)

- Hormones in women (65 percent)

- Not eating (57 percent)

- Weather (53 percent)

- Sleep disturbances (50 percent)

- Odors (44 percent)

- Neck pain (38 percent)

- Lights (38 percent)

- Alcohol (38 percent)

- Smoke (36 percent)

- Sleeping late (32 percent)

- Heat (30 percent)

- Food (27 percent)

- Exercise (22 percent)

- Sexual activity (5 percent)

Obesity has been associated with an increased frequency and severity of migraine [17-20].

Are there ways I can tell a tension headache from a migraine headache? While the features of migraine and tension headache overlap, the clinical features that appear to be most predictive of migraine include nausea, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to sound, and worsening of symptoms by physical activity [21, 22]. Food triggers are also more common with migraine than tension-type headache.

The International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria for migraine with and without aura are as follows [14]:

Migraine without aura — Migraine without aura is a recurrent headache disorder that fulfills the following criteria [14]:

- Headache attacks last 4 to 72 hours

- Headache has at least two of the following characteristics: unilateral location; pulsating quality; moderate or severe intensity; aggravation by routine physical activity

- During headache at least one of the following occurs: nausea and/or vomiting; photophobia and phonophobia

- At least five attacks occur fulfilling the above criteria

- History, physical examination, and neurologic examination do not suggest any underlying organic disease

Migraine with aura — In migraine with aura, attacks include the transient appearance of focal neurologic symptoms that usually develop gradually over 5 to 20 minutes and last for less than 60 minutes. A headache that has the features of migraine without aura begins during the aura or follows the aura within 60 minutes.

Although too detailed for this overview, it is important to know that other types of migraines exist, including ‘Menstural migraines’ (a migraine headache that occurs in close temporal relationship to the onset of menstruation), ‘Basilar-type migraine’ (often present as difficulty speaking, ear ringing, double vision, decreased hearing then followed by a typical migraine headache), etc.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=yZr9Joe85wg

The purpose of this overview is for informational purposes only not as a tool for diagnosis, treatment, or management. If you experience any types of head pain, visual disturbances, nausea and vomiting it is imperative that you seek immediate consultation with a physician for treatment as many other diseases or injuries can cause similar signs and symptoms and may be life threatening. Consult with your physician regarding diagnosis, management, and prevention.

REFERENCES

- Charles A. Advances in the basic and clinical science of migraine. Ann Neurol 2009; 65:491.

- Charles A. Vasodilation out of the picture as a cause of migraine headache. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:419.

- Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:454.

- Sessle BJ, Hu JW, Dubner R, Lucier GE. Functional properties of neurons in cat trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (medullary dorsal horn). II. Modulation of responses to noxious and nonnoxious stimuli by periaqueductal gray, nucleus raphe magnus, cerebral cortex, and afferent influences, and effect of naloxone. J Neurophysiol 1981; 45:193.

- Wise SP, Jones EG. Cells of origin and terminal distribution of descending projections of the rat somatic sensory cortex. J Comp Neurol 1977; 175:129.

- Sarchielli P, Alberti A, Floridi A, Gallai V. Levels of nerve growth factor in cerebrospinal fluid of chronic daily headache patients. Neurology 2001; 57:132.

- Lance JW, Anthony M. Some clinical aspects of migraine. A prospective survey of 500 patients. Arch Neurol 1966; 15:356.

- Merikangas KR, Risch NJ, Merikangas JR, et al. Migraine and depression: association and familial transmission. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:119.

- Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001; 41:646.

- Stewart WF, Shechter A, Rasmussen BK. Migraine prevalence. A review of population-based studies. Neurology 1994; 44:S17.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007; 68:343.

- Charles A. The evolution of a migraine attack – a review of recent evidence. Headache 2013; 53:413.

- Kelman L. The premonitory symptoms (prodrome): a tertiary care study of 893 migraineurs. Headache 2004; 44:865.

- Cutrer FM, Huerter K. Migraine aura. Neurologist 2007; 13:118.

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 Suppl 1:9.

- Hansen JM, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, et al. Migraine headache is present in the aura phase: a prospective study. Neurology 2012; 79:2044.

- Martin VT, Behbehani MM. Toward a rational understanding of migraine trigger factors. Med Clin North Am 2001; 85:911.

- Kelman L. The triggers or precipitants of the acute migraine attack. Cephalalgia 2007; 27:394.

- Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology 2006; 66:545.

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Obesity is a risk factor for transformed migraine but not chronic tension-type headache. Neurology 2006; 67:252.

- Bigal ME, Tsang A, Loder E, et al. Body mass index and episodic headaches: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1964.

- Smetana GW. The diagnostic value of historical features in primary headache syndromes: a comprehensive review. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2729.

Recent Posts

My Head Hurts! All About Headaches and Your Relief Options

March 18, 2020Workplace Pain Relief and Management: The Best Ways to Diminish Pain

February 12, 2020Why Does My Shoulder Hurt? How to Relieve the Pain?

January 14, 2020Share this Post

Recent Posts

My Head Hurts! All About Headaches and Your Relief Options

Workplace Pain Relief and Management: The Best Ways to Diminish Pain